Komagata Maru was a steamship owned by the Shinyei Kisen Goshi Kaisya of Japan.

Komagata Maru was a steamship owned by the Shinyei Kisen Goshi Kaisya of Japan.

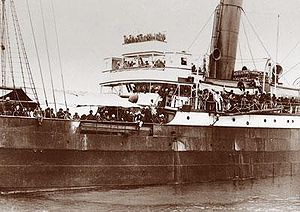

In 1914 the Komagata Maru was central to what became known as the Komagata Maru Incident, which involved 354 passengers from India who unsuccessfully attempted to immigrate to Canada. To accommodate the passengers, the lower deck was cleaned and fitted with latrines and wooden benches. The ship sailed back to India where, after disembarking from the ship, some of the passengers were killed in an incident with police authorities.

The Canadian government’s first attempt to restrict immigration from India was to pass an order-in-council on January 8, 1908, that prohibited immigration of persons who “in the opinion of the Minister of the Interior” did not “come from the country of their birth or citizenship by a continuous journey and or through tickets purchased before leaving their country of their birth or nationality.” In practice this applied only to ships that began their voyage in India, as the great distance usually necessitated a stopover in Japan or Hawaii. These regulations came at a time when Canada was accepting massive numbers of immigrants (over 400,000 in 1913 alone – a figure that remains unsurpassed to this day), almost all of whom came from Europe.

The visions of men are widened by travel and contacts with citizens of a free country will infuse a spirit of independence and foster yearnings for freedom in the minds of the emasculated subjects of alien rule.

Gurdit Singh

Punjabis were facing immigrating to Canada due to certain exclusion laws. Gurdit singh wanted to circumvent these laws by hiring a boat to sail from Calcutta to Vancouver. His aim was to help his compatriots whose previous journeys to Canada had been blocked.

Though Gurdit Singh was apparently aware of regulations when he chartered the Komagata Maru in January 1914, he continued with his purported goal of challenging the continuous journey regulation and opening the door for immigration from India to Canada.

Passengers

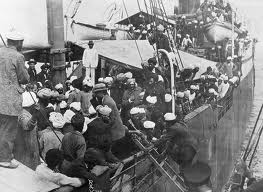

The passengers consisted of 340 Sikhs, 24 Muslims, and 12 Hindus, all British subjects. One  of the Sikh passengers, Jagat Singh Thind, was the youngest brother of Bhagat Singh Thind, an Indian-American Sikh writer and lecturer on “spiritual science” who was involved in an important legal battle over the rights of Indians to obtain U.S. citizenship.

of the Sikh passengers, Jagat Singh Thind, was the youngest brother of Bhagat Singh Thind, an Indian-American Sikh writer and lecturer on “spiritual science” who was involved in an important legal battle over the rights of Indians to obtain U.S. citizenship.

Voyage

Departure from Hong Kong

Hong Kong became the point of departure. The ship was scheduled to leave in March, but Singh was arrested for selling tickets for an illegal voyage. He was later released on bail and given permission by the Governor of Hong Kong to set sail, and the ship departed on April 4 with 165 passengers. More passengers joined at Shanghai on April 8, and the ship arrived at Yokohama on April 14. It left Yokohama on May 3 with its complement of 376 passengers, and sailed into Burrard Inlet, near Vancouver, on May 23. “This ship belongs to the whole of India, this is a symbol of the honour of India and if this was detained, there would be mutiny in the armies,” a passenger told a British officer. The Indian Nationalist revolutionaries Barkatullah and Balwant Singh met with the ship en route. Balwant Singh was head priest of the Gurdwara in Vancouver and had been one of three delegates sent to London and India to represent the case of Indians in Canada. Ghadarite literature was disseminated on board and political meetings took place on board.

Arrival in Vancouver

When the Komagata Maru arrived in Canadian waters, it was not allowed to dock. The first immigration officer to meet the ship in Vancouver was Fred “Cyclone” Taylor. The Conservative Premier of British Columbia, Richard McBride, gave a categorical statement that the passengers would not be allowed to disembark, as the then–Prime Minister of Canada Sir Robert Borden decided what to do with the ship. Conservative MP H.H. Stevens organized a public meeting against allowing the ship’s passengers to disembark and urged the government to refuse to allow the ship to remain. Stevens worked with immigration official Malcolm R. J. Reid to keep the passengers off shore. It was Reid’s intransigence, supported by Stevens, that led to mistreatment of the passengers on the ship and to prolonging its departure date, which wasn’t resolved until the intervention of the federal Minister of Agriculture, Martin Burrell, MP for Yale—Cariboo.

Meanwhile a “shore committee” had been formed with Hassan Rahim and Sohan Lal Pathak. Protest meetings were held in Canada and the United States. At one, held in Dominion Hall, Vancouver, it was resolved that if the passengers were not allowed off, Indo-Canadians should follow them back to India to start a rebellion (or Ghadar). A British government agent who infiltrated the meeting wired London and Ottawa to tell them that supporters of the Ghadar Party were on the ship.

The shore committee raised $22,000 as an installment on chartering the ship. They also launched a test case legal battle under J. Edward Bird’s legal counsel in the name of Munshi Singh, one of the passengers. On July 6, the full bench of the B.C. Court of Appeal gave a unanimous judgement that under new orders-in-council, it had no authority to interfere with the decisions of the Department of Immigration and Colonization. The Japanese captain was relieved of duty by the angry passengers, but the Canadian government ordered the harbor tug Sea

Lion to push the ship out to sea. On July 19, the angry passengers mounted an attack. The next day the Vancouver newspaper The Sun reported: “Howling masses of Hindus showered policemen with lumps of coal and bricks… it was like standing underneath a coal chute”.

Departure from Vancouver

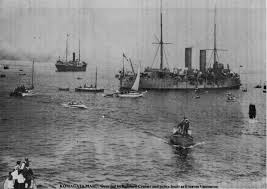

The government also mobilized HMCS Rainbow a former Royal Navy ship under the command of Commander Hose, with troops from the 11th Regiment Irish Fusiliers of Canada, 72nd Regiment “Seaforth Highlanders of Canada”, and the 6th Regiment “The Duke of Connaught’s Own Rifles”. In the end, only 20 passengers were admitted to Canada, since the ship had violated the exclusion laws, the passengers did not have the required funds, and they had not sailed directly from India. The ship was turned around and forced to depart on July 23 for Asia.

Return to India

The Komagata Maru arrived in Calcutta on September 27. Upon entry into the harbour, the ship was stopped by a British gunboat, and the passengers were placed under guard. The government of the British Raj saw the men on the Komagata Maru not only as self-confessed lawbreakers, but also as dangerous political agitators. When the ship docked at Budge Budge, the police went to arrest Baba Gurdit Singh and the 20 or so other men that they saw as leaders. He resisted arrest, a friend of his assaulted a policeman and a general riot ensued. Shots were fired and 19 of the passengers were killed. Some escaped, but the remainder were arrested and imprisoned or sent to their villages and kept under village arrest for the duration of the First World War. This incident became known as the Budge Budge Riot.

Ringleader Gurdit Singh Sandhu managed to escape and lived in hiding until 1922. He was urged by Mahatma Gandhi to give himself up as a ‘true patriot’; he duly did so, and was imprisoned for five years.

Significance

The Komagata Maru incident was widely cited at the time by Indian groups to highlight discrepancies in Canadian immigration laws. Further, the inflamed passions in the wake of the incident were widely cultivated by the Indian revolutionary organisation, the Ghadar Party, to rally support for its aims. In a number of meetings ranging from California in 1914 to the Indian diaspora, prominent Ghadarites including Barkatullah, Tarak Nath Das, and Sohan Singh used the incident as a rallying point to recruit members for the Ghadar movement, most notably in support of promulgating plans to coordinate a massive uprising in India. Lack of support from the general population caused these plans to come to nothing.